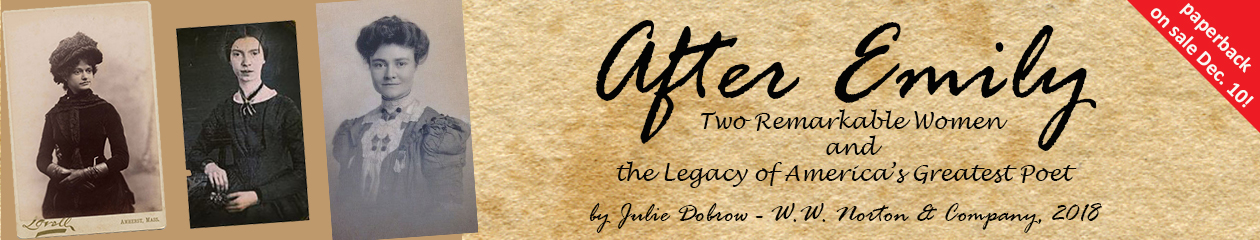

As excitement builds over the total solar eclipse that will be visible in much of the United States this summer, Julie looks through the other end of the telescope back at astronomer David Peck Todd, one of the subjects of Outside Emily’s Door, and his frustrating lifelong quest to view grand celestial events.

https://www.amherst.edu/amherst-story/magazine/issues/2017-summer/the-star-crossed-astronomer

The Star-Crossed Astronomer

Across the world he traveled

on the trail of the elusive

total solar eclipse. But again and again,

clouds got in his way.

Total solar eclipses are visible from Earth every year, but the chance to see one from any specific point is rare. In Amherst, for example, totality comes around once in about 375 years. While a lunar eclipse tracks across an entire hemisphere, the track of a typical solar eclipse is only 60 or 70 miles wide. So the celestial happening to which many Americans will be treated this summer is quite unusual: the first total solar eclipse to be visible across a large swath of the continental United States since 1918.

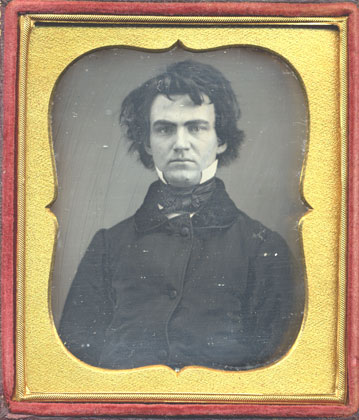

David Peck Todd, class of 1875, made a career of trying to view such events. As an Amherst professor, he spent decades chasing eclipses around the globe. While this work brought him some acclaim, it also surrounded him with notoriety. “His exploits,” noted Amherst Professor F. Curtis Canfield ’25 in a somewhat facetious tribute, “successful or not, always got headlines in the national press; Amherst had no need of a publicity department with Davy Todd on the faculty.”

In fact, Todd’s lack of success in recording the elusive total solar eclipse over the course of many expeditions around the world might have contributed to his forced leave of absence from Amherst 100 years ago, in 1917. Elemental forces—those derived from nature and those emanating from humankind—thwarted Todd’s best and considerable efforts. His profound frustration with these failures no doubt fueled the downward spiral into which this once-promising talent dizzyingly tumbled.

Born in upstate New York in 1855, Todd was a precocious intellect, a gifted organist and a tinkerer with a bent for mechanical invention. He enrolled at Columbia University as a 15-year-old, then transferred to Amherst because of its astronomy program and observatory. After graduating he worked for the U.S. Naval Observatory and the U.S. Nautical Almanac Office in Washington, D.C., where he met and married Mabel Loomis, an effervescent young woman with ambitions of her own. Mabel would become one of Emily Dickinson’s first editors, publishing the initial volume of Dickinson’s poetry in 1890. Mabel would also, infamously, have a 13-year-long affair with Austin Dickinson, class of 1850, treasurer of the College and brother of the poet.

David Todd’s interests in astronomy were far-ranging. As an undergraduate he made a name for himself by observing Jupiter’s satellites at the times of their eclipses. When he returned to Amherst in 1881 as an instructor and director of the observatory, he extended his work to studying many types of solar activities. He traveled to California in 1882, for example, to head observations of the Transit of Venus for the Lick Observatory. This rare astronomical occurrence, in which the full outline of Venus can be seen as it passes between the sun and Earth, happens just twice each century. This was Todd’s only chance to see and photograph the event, and he left Amherst for two months in its pursuit.

While in California he began developing ways to take rapid series of photographs that, when put together in a kind of flipbook, could capture movement of a solar event. He tinkered with other equipment too: On one of his first eclipse expeditions, in 1887, he took the unusual step of employing multiple telescopes and spectroscopes. His hope was to enable a more comprehensive and precise view of the eclipse, ostensibly eliminating human error. Todd worked to refine this nascent technology over several expeditions.

In 2004, during this century’s Transit of Venus, astronomers Anthony Misch and Bill Sheehan found all of Todd’s stills from 1882 and animated them, a feat that would have thrilled him. Indeed, Todd’s most lasting contribution to astronomy may be his work to simulate animation—now a fundamental method for studying eclipses. Misch and Sheehan consider his images from 1882 “superb,” and the most complete record of that astronomical event. But Todd’s success with the Transit of Venus photography was an anomaly: It may be that, in the annals of astronomy, he is better known for his failures.

Ever since the invention of photography, astronomers have seen its utility. English scientist John William Draper is credited with taking the first detailed photograph of the moon, in 1840. In 1851 astronomers at the Royal Prussian Observatory became the first to photograph a total solar eclipse. In the decades that followed, photos of total solar eclipses remained quite unusual. The sightings were rare, and the slow shutter speeds of early cameras made it difficult to capture the rapid progression toward totality. But Todd believed his propensity for invention, paired with his proclivity for distant travel, would enable him to accomplish what others had not.

Beginning in 1878, Todd led a series of expeditions to observe solar eclipses. He went on a dozen of them in all, traveling to five continents and more than 30 countries. Mabel and their only child, Millicent, accompanied him on several. There were three expeditions to Japan and two to Libya. Todd also led teams to Angola, Chile, Brazil and other countries throughout Europe, Asia and South America.

The 1896 trek to Japan was known as the “Amherst Expedition.” Funded by multimillionaire railroad magnate Arthur Curtiss James, class of 1889, David and Mabel departed on their journey serenaded by the Amherst Glee Club (which, Mabel noted, culminated its performance with a rousing “Amherst yell!”). They set sail from San Francisco on James’ yacht, the Coronet, across the Pacific to Yokohama. James also financed Todd’s 1901 “Amherst Expedition to the Dutch East Indies.”

Each trip included travels to neighboring countries, visits with people of diverse cultures and the collection of thousands of artifacts, which were carefully packed up and sent home to Amherst. Todd devoted years to planning and raising money. He tinkered with heavy equipment, shipped it around the globe and reconstructed it on remote mountaintops. It often took months for the equipment to reach these locations. There was, however, one thing he could not control. With few exceptions, on every evening when totality approached, the clouds closed in. So consistently did this happen that once, after Todd’s death, Millicent attended a dinner and met a famous British astronomer who acknowledged her father with the moniker “Professor Todd of the Cloudy Eclipses!”

While Todd never made much professional gain from the eclipse expeditions, Mabel certainly did. With the rare ability to spin any experience, she used much of what she saw and heard on these travels to become a nationally recognized newspaper and magazine correspondent. She wrote two books based on the failed expeditions, Corona and Coronet and Tripoli the Mysterious. For Millicent, the expedition to Peru in 1907 became the basis of her doctoral dissertation (she was the first woman to receive a Ph.D. in geography and geology from Harvard) and subsequent publication, Peru, A Land of Contrasts. All the while, David Todd’s main goal of photographing a clear eclipse remained unrealized.

Weather permitting, on Aug. 21, 2017, sky-gazers all across North America, as well as in parts of South America, Asia, Africa and Europe, will get to see a partial solar eclipse. And viewers across 14 U.S. states, from Oregon to South Carolina, will be within the path of totality; they’ll have the rare chance to see a total solar eclipse. A team from Google and the University of California, Berkeley, has recruited citizen scientists to submit, via a free app, footage filmed on smartphones. Edited together, this footage will form a “megamovie,” ideally documenting the entire progression of the eclipse, to show how the corona changes over time.

A century ago, scientists tried to document the same thing. The expedition to photograph the solar eclipse of 1914 was to be a novel experiment. Todd and several other astronomers hoped to take photos at different points along the eclipse’s path in Eastern Europe, with a goal of putting them together to better understand aspects of the phenomenon. The Todd family gallantly traveled to St. Petersburg, Russia, only months after Mabel had recovered from a stroke that left her temporarily paralyzed. Fortunately the Todds were diligent—some would say self-promotional—about speaking with reporters, and Millicent typed up more than 150 pages of her journal from this epic voyage. Without those accounts, we would have no record of it.

Having been stymied by the weather many times before, Todd’s plan for the Russia expedition was to fly above any cloud cover in an “aeroplane” and photograph the eclipse from the air. As he told reporters, “This will enable me to learn whether the bands of light visible only during an eclipse come from the corona itself or are reflected by the gasses given off by the sun.” (He was probably referring to what are known as “shadow bands,” rapidly moving bands of light visible before and after a solar eclipse. In the 19th century scientists theorized that these were caused by diffraction from the sun; we now know them to be caused by turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere.) Todd—a founding member of the Aero Club of America who began a chapter at Amherst (the first at any college)—had great hopes for how aviation could be used in pursuit of astronomical photography.

But this time it was not Mother Nature that intervened; it was World War I.

As tensions heightened throughout Eastern Europe, the Todd family, along with other astronomers who’d arrived for the eclipse, were told they needed to leave, quickly. “Wakened by the wail of woman in the grey dawn,” wrote Millicent, “an astronomer from a far country, marooned in a great city by impending war, arose to finish his calculations of the sun’s total eclipse he had come thousands of miles to see.”

Unfortunately, there was no airplane in which to fly, and, as Todd later recounted to The Amherst Student, the outbreak of war meant that “railroad traffic was totally interrupted, and my instruments … did not arrive.” The Todds made a hasty and perilous retreat across the continent, waiting hours for trains that never came, frequently changing their itinerary to avoid the spreading conflict. When U.S. colleagues lost contact with Todd, the Aero Club of America unsuccessfully appealed to Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan to help find him. One headline screamed, “Prof. David Todd Lost in Russia.” Other articles suggested the “Amherst savant” might have been arrested in the course of his scientific mission.

In truth, Todd and his family were neither lost, nor detained, nor missing. They were just trying to get home. Eventually they made it to Scandinavia and undertook an ocean voyage to England, dodging German U boats. Mabel summarized the expedition to Millicent, who recorded it for posterity: “Another eclipse tragedy.”

David Peck Todd came to see the escape from Russia as part of a pattern—one that began in 1882, when his first office at

Amherst burned to the ground. He told his daughter that he should have recognized the Walker Hall fire for what it was: the leitmotif of his life. Indeed, elemental forces stymied Todd at every turn, “whether fire, which destroyed his calculations, the foundation of his next discovery and building-store of his astronomical reputation,” Millicent wrote, “or the cosmos, which rewarded the years of preparations for observing a total eclipse of the sun, each time, by shutting it out.”

Todd turned his professional attention to ever-stranger pursuits. He became convinced that intelligent life existed on Mars and obsessed with radio communication as a way to connect with Martians. Once again he tinkered, going up in hot air balloons with equipment he’d designed to send signals to Mars and to pick up any signals that Martians might send back.

Todd was hardly the only person experimenting with extraterrestrial signaling—Guglielmo Marconi, for instance, was also discussing this possibility—but Todd’s convictions seemed to run deeper than most. In 1907 The New York Times quoted Todd’s belief that there was probably “something like human intelligence on Mars,” a conclusion he came to based “purely upon inferential indications.” Not surprisingly, he faced derision from his colleagues.

Todd wrote one article, for some unknown publication, headlined “What if People DO Ridicule You!” In his words: “Professor Todd is an astronomer who has done work of genuine scientific value, yet because he was not afraid to experiment with novel ideas, he has been criticized, misrepresented and ridiculed. For years the newspapers have printed jokes about him. They have guyed him for his alleged belief that he would sometime be able to communicate with Mars.” The article goes on to

justify his theories of extraterrestrial intelligent beings and the need to contact them.

His increasingly odd behavior was much more than a departure from scientific rigor—it indicated a departure from sanity. He began to skip classes and meetings. In a 1954 Chapel talk, Professor Canfield related that even when Todd, the “modern Marco Polo,” was in Amherst and not chasing eclipses, “work in his courses worried neither the professor nor his students. It is now legend that all one needed to do to pass astronomy was to appear occasionally at the Todd house for afternoon tea.”

Though the record is scant, Mabel and Millicent noted in their diaries that Todd began to sleep little, at odd times and in odd places—sometimes across a tabletop. He spent money lavishly. He sent Millicent on errands that left her questioning his mental state. He would ask her to fetch something from a person who turned out not to exist, and send her to nonexistent addresses to find friends he wished to see. “I got very tired from all of those wild goose chases,” she noted.

Yet it still came as a surprise to the Todds when, in 1917, President Alexander Meiklejohn wrote to say the College’s board of trustees (including family friend and benefactor Arthur Curtiss James) had voted unanimously to grant Todd an “indefinite” leave of absence. “On the whole, I think it would be better for us, and possibly for you, if your leave of absence were continued,” wrote Meiklejohn. “The work in astronomy has not gone well and has been pretty thoroughly out of harmony with the general scheme of instruction.”

The Todds packed up their home in the College-owned Observatory House (now faculty apartments on Snell Street) and left Amherst behind, along with all the College and town had meant to them, in the summer of 1917.

Todd’s subsequent projects included attempts to find a solution to the sun breaking in two (something he was certain would occur during his lifetime) and a plan to crack a “secret code devised by Captain Kidd” and “locate treasure” buried near Deer Isle, Maine. By 1922 his progressively erratic behavior and increasingly fantastic ideas led Mabel and Millicent to the excruciating decision to institutionalize him. He was in and out of mental institutions and nursing facilities until his death in 1939.

In 1932 Millicent and husband Walter Van Dyke Bingham took Todd to Maine for what would be his last eclipse. This time, the viewing was clear. Writing about that night years later, Millicent said, “I gained a flash of understanding of his blighted life, which filled my heart with compassion and my eyes with tears … a glimpse of understanding of what a series of cloudy eclipses, failures, meant to my father, who had put all he had into the preparation for success, time after time, betrayed by his own cosmos.”

Todd is buried in Amherst’s Wildwood Cemetery, where the engraving on his tombstone depicts an eclipse, the sun’s corona clearly visible. The irony of the image would not have been lost on this complicated, brilliant and troubled man.

This August, as Amherst alumni across the United States point cell phone cameras toward the path of the total solar eclipse, they should pause and think of David Peck Todd. He would have applauded the effort—and urged them to take some video, too.

Julie Dobrow, a Tufts University professor, is the author of the forthcoming bookOutside Emily’s Door: Mabel Loomis Todd, Millicent Todd Bingham and the Making of America’s Greatest Poet (W.W. Norton).