10/30/18

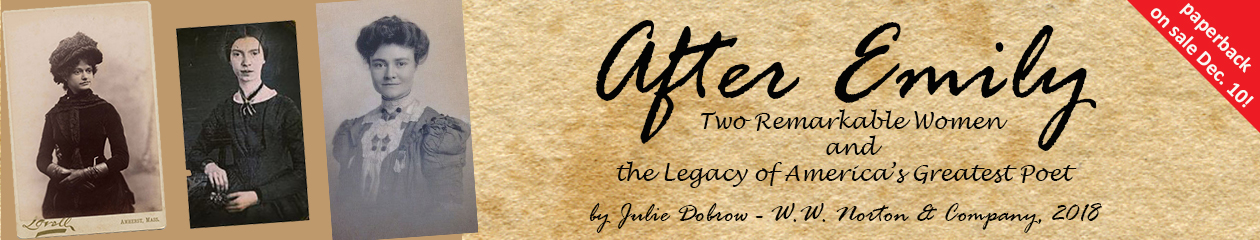

Today is the day I’ve long waited for. After Emily is officially published!

Throughout the time I’ve been working on this book, I’ve kept a journal about the process. This has been a kind of meta-experience, writing about the writing. I’m very glad I did this because it’s been a way to think through and process these intertwined and complicated stories. I’ve also learned a lot about writing, and about myself.

This was the very first entry in the journal:

3/3/11

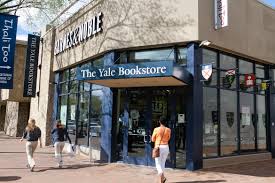

Today I feel like I really started the project for the first time. The microfilms I’d requested from Yale on inter-library loan FINALLY arrived after weeks of waiting, and I spent 7 hours looking at them. I went through 4 years’ of Mabel’s diaries; didn’t even complete a whole reel. This is going to take me a very long time.

It was both about learning more about her day-to-day existence and also about starting to figure out how to do this work. And also about starting to make sense of it. I decided I should start this file to help me process the process.

It did take me a long time to go through the materials, to do the research and to go through the processes of writing, re-writing and editing that were necessary to get this book done. But I’m so glad I did it.

I looked back to see whether I could find anything either Mabel or Millicent had written when their respective books were published. In November of 1890, Mabel had initially written of her excitement when she received the first few pre-publication copies of the first edition of Emily’s poems. And then on publication day, she wrote, “Today Emily’s book of Poems is issued. I had more copies since Sat, but the bookstores got them today. Her gifts are now shared with the world.”

In 1909, Mabel’s mother was very ill, and Mabel wrote in her journal about how her mother was “living to wait to see” Mabel’s most recent book – A Cycle of Sunsets – published. Despite her conflicted relationship with her mother, it seemed important to Mabel that her mother live to see this work. This is interesting because it wasn’t Mabel’s first book (by 1910 she had already published four of her own books as well as three edited volumes of Emily’s poetry and two edited books of her letters).

I’m not entirely sure why she wanted Molly to be able to see this book (she did – she didn’t die until the fall of 1910 and the book was published in the spring). Perhaps it’s because more than any of Mabel’s other books, this one was about nature, and reviewers had commented, among other things, that “Mabel Loomis Todd is a worthy successor to Thoreau.” The link to Henry David Thoreau would be one that Molly greatly appreciated, the Wilder family having been intimate friends with the Thoreaus. Molly always believed – and instilled in both her daughter and her granddaughter – that this link between the Wilder and Thoreau families was important. A book in the tradition of Henry David Thoreau (A Cycle of Sunsets is a series of essays about sunsets over the course of a year) would naturally be a book that Mabel’s mother would endorse. Mabel would have believed that this book would earn her the kind of whole-hearted praise from her mother she’d long sought and seldom received, despite all her many achievements.

And for Mabel, who wanted more than anything else in life to be known and remembered as a great writer, the idea that she’d written a book in the tradition of Thoreau would also have been tremendously appealing.

I wasn’t able to find much that Millicent had written about the publication of any of her books. This is partially because for Millicent, the publication of her four Dickinson books was so fraught with conflicted feelings and so fraught with the “battles with Harvard” that having them finally published must have seemed more a relief than a triumph. And I think it’s partially because Millicent was actually working on the four Dickinson books at the same time, an overwhelming task in itself. But she apparently also was thinking about whether she could also write some of the stories she most wanted to tell, in addition to fulfilling the promises she made to her mother about getting the Dickinson work done. In 1938, for example, she pondered, “These MSS, lying around, unpublished – warbook, debut book, geographic controls in Peru, Mamma’s edited Emily Dickinson poems – to name a few. The deadlock must somehow be broken.”

For Millicent the deadlock got broken when her sense of filial responsibility won out and she worked on the Dickinson books rather than the others she’d clearly been thinking about.

So today, on the publication date of my own book about Mabel and Millicent, I find myself wondering, as I often do, what they would think about it all…

In a few hours I will be off to New Haven to begin my book tour. It seems so appropriate to me to begin this part of the journey where so much of the journey of this book took place: at Yale, home of the Todd/Bingham Family Papers.