10/22/18

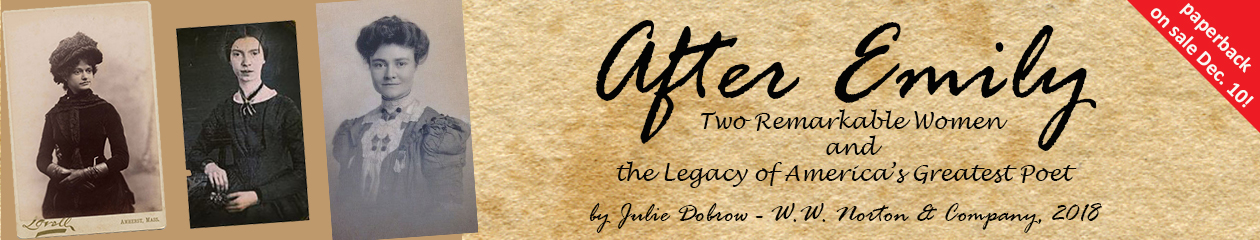

In the run-up to publication of After Emily, many people have been asking me how long it took me to work on this book. When this question comes from people who know a little about Mabel and Millicent, I think it has to do with knowledge that there was a LOT of material to go through (721 boxes of primary source material at Yale, alone!) But the vast majority of people who ask me this question seem to be asking it not because they’re wondering about the research process, but about the writing.

I know that for many people, writing takes a long time. It’s a laborious effort. Some people I know who are excellent writers struggle over each word, every phrase. You’d never know it from the fluid end result.

I’ve been lucky. Writing comes easily to me and always has. Which is not to say that the end product doesn’t take a long time to come to – it does. In writing After Emily I’ve learned more than ever about ways in which the rewriting process can take a lot of time. To make a sentence unspool in a way that readers will want to linger on it as if touching a soft and delicate thread, takes care and thought.

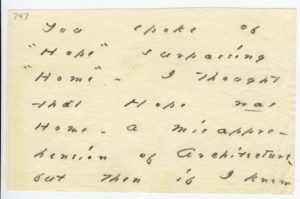

The three women at the center of my book – Emily, Mabel and Millicent – were all excellent writers. We don’t hear very much from Emily about her process. There are some letters, to Sue and to Thomas Wentworth Higginson. We have her “scraps” and the different alternatives she offered in word choice, punctuation and capitalization as suggestions about how she composed. We don’t really know how long she labored on any particular poem, or why she made the decisions she made, or even if some of what ended up getting published were truly her decisions or those of her various editors’.

For Mabel, composition in words came easily. She wrote a lot about writing and her process. In 1886, for instance, she wrote, “Expression in writing is absolutely easy and natural to me, and is always a delight…but I say, unconsciously to myself a good that there is plenty of time, you are ripening and mellowing and strengthening all the time, and you…yet write nobly.” (She was never one to be modest!) The editing process was one she took seriously; it was never easy, but even she often had to admit that her very florid prose was made better by the slow process of going back over it.

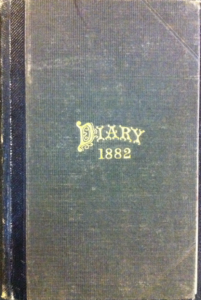

Millicent was a methodical but thoughtful writer. In the summer of 1908, when she was 28, she became very ill with diphtheria and a heart condition, and moved back home to Amherst so her parents could help take care of her. She kept a special journal during this time when, for several weeks, she was literally not even allowed to sit up, amusing herself by writing her observations on the little things she saw and heard: birds outside her window, spiders spinning webs, clouds. On June 21 she wrote, “Why must I always write down what I feel to be satisfied? Is it a prediction of a future message, or is it only a habit?” In fact, it turned out to be both: like her mother, Millicent was a lifelong journal and diary keeper, someone who often felt the need to write as a way of processing what she saw or heard or felt.

Anyone who has ever kept a diary or journal knows the indulgence of reading back over it. You marvel at the accomplishments, the moments of insight; you despair over the disappointments, the moments of ignorance. You look back with the gift of hindsight and wonder how you possibly could have thought or felt what you did at the time. You see how you have grown. You notice the themes and patterns of your life, and you are incredulous over the passage of time. In her final years, Millicent spent significant time reading over her own diaries and journals, as well as reading Mabel’s. But for Millicent this wasn’t simply a passing indulgence; it was a painful and time-consuming obsession. While she didn’t find the answers she sought to the questions that plagued her, or the solace she hoped she’d uncover, she unquestionably knew that both for herself and for her mother, the time spent writing had been invaluable.

So when people ask me how long it took me to write After Emily, I have to smile. The actual time I spent researching or writing or rewriting isn’t nearly as important as the journey it’s been to get to know these three remarkable women and figure out how best to convey them to readers.

Greetings Julie Dobrow,

Thank you for your dedicated research and writing on the legacy of Emily Dickinson.

I grew up in New England, but my parents were from rural Canada. I did not know about the extent of classism on the workings of life in New England; although you write about an earlier time, I’m guessing that not much has changed.

Your book shines light on a number of areas: the writhing intricacies of the creative process, the eternal conflict between introverts (Millicent) and extroverts (Mabel), the grappling that is all too common between female family members, and it exquisitely documents the difficulties that women had—and still have—when it comes to the expression of selfhood.

That’s a lot to take on, and you did it well. Perhaps you hear that enough since the publication of you book, but I thought I’d throw my two-bits in!

As for why Emily chose reclusion, I wonder if she may have been born as what we used to call hermaphrodite—now called intersex. I’m sure I’m not the first to speculate about this; it would explain why she closed off as she got older. According to what I have read, physical ambiguity can become more problematic with age.

Thanks again for your contribution to an understanding of human nature.