4/16/19

Today is Austin Dickinson’s birthday. For years after his death, Mabel would mark this day with a combination of reverence and sadness. I’d like to mark this day by spending a little time pondering this enigma of a man who was so central to the story of After Emily, and yet about whom there are still so many unanswered questions.

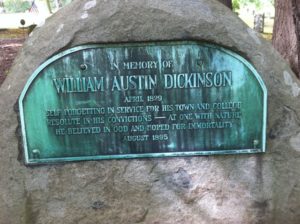

We know that Austin was widely heralded as having a keen intelligence and as being industrious and dedicated. Though a graduate of both Amherst College and Harvard Law School, he “…never attained prominence as a practitioner before the courts,” noted his obituary in the Springfield Republican. “In fact he avoided the trial of cases, but he was a singularly valuable, clear-headed and conscientious, and his advice and assistance were much sought in the community….” As Richard Sewall pointed out, Austin paid $500 to a man to take his place in the army during the Civil War. And though you’d think that Austin’s prominence in Amherst through his family name and his many acts of civic engagement would have made him a logical candidate for political office, he “…never held a political office, and no town office of importance, except that of moderator, which for nearly 20 years he had held almost continuously.”

But was Austin’s reluctance to practice law outside of his father’s firm and his reticence to run for political office a direct function of the conflicted relationship he seemed to have with his father? Austin acceded to Edward’s requests (demands?) that he stay in Amherst, that he join the family law firm, that he move into the house built for him next door to his family’s home, but he clearly didn’t follow in his father’s legal or political footsteps. Was Austin’s avoidance of military duty an act of bravery or a deed of civil disobedience he didn’t dare to state publicly? Though it’s not clear that 19th century politics was any more devoid of scandal than politics today, was Austin Dickinson’s life so riddled with “issues” that it would have precluded a successful political run – or would he have been as unscathed by it all as he seemed to be in his personal life?

Austin was, in so many ways, “the most influential citizen of Amherst,” as his obituary noted. Polly Longsworth has catalogued his many civic bequests to the town, including his work with banks, with helping to bring gas and electricity to Amherst, his role in the First Church and his efforts to create Wildwood Cemetery. “No man in Amherst has done more to beautify the town,” stated the writer of his obituary; indeed, as president of the village improvement association, Austin helped to bring Frederick Law Olmsted to Amherst to design the town common, a place which remains a vibrant part of the town to this day. Austin served as treasurer of Amherst College for many years and was so involved in helping to improve its buildings, grounds and financial affairs that these activities merited an entire paragraph in almost any published description of him. “His love for Amherst was so strong he did not care to spend a vacation elsewhere and he always expressed the satisfaction he had on returning to the town from a trip of even a few days duration,” stated the writer of his obituary (no doubt with at least a prompt from Austin’s surviving family members, who also, no doubt, were at very least conflicted in their relationships with him following all the years of the Mab-stin pairing).

But was Austin’s unwillingness to leave Amherst so very different from his sister’s eventual unwillingness to leave the confines of her family home? While there’s no doubt his dedication to his town and to his college were true and sincere, were they actually also another indication of his enormous reluctance to leave? And was this desire to stay put also suggestive of his averseness to change, a sign Mabel should have read as a not-so-subtle warning that Austin would never do what he would have needed to do for the two of them to be together as they so often wrote they needed to be?

We know that Austin and Emily shared a special bond. Quite apart from Mabel’s reporting of this relationship (which might well have been tinted by the power of her relationship with Austin and her own self-interested interpretation of the Dickinson filial bond) we have the record of Austin and Emily’s correspondence, letters that document their clever repartee, their shared fascination with the natural world and their somewhat skeptical interpretations of their parents.

But what was the nature of Emily’s relationship with Susan Huntington Gilbert and what happened when she became the object of Austin’s desire? In what ways might have Austin’s relationship with Emily changed then? And when Austin turned his ardor to Mabel, how did the dynamic shift between Emily and Austin?

Finally, we’ve heard from both Mabel and from Emily that despite Austin’s austere exterior and intense practicality, he was, in fact, a thoughtful, romantic – and even poetic soul. In her introduction to the second edition of Emily Dickinson’s letters Mabel wrote that Austin “was a poet too, only the poetry of his temperament did not flower in verse or rhyme, but in an intense and cultivated knowledge of nature, in a passionate joy in the landscapes seen from Amherst hill- tops.” After Austin sent some actual verse he’d composed in 1853 to his sister, Emily wrote him, “Austin is a Poet, Austin writes a psalm. Out of the way, Pegasus, Olympus enough ‘to him,’ and just say to those ‘nine muses’ that we have done with them! Raised a living muse, ourselves, worth the whole nine of them.”

But was Brother Pegasus’ poetic soul confined by the roles he felt forced to play in life? As Sewall suggested, the one publication Austin was known to have penned – an address at the 150th anniversary of the First Church in 1889, “was strictly local, written in the line of duty.” Did the muffled poet find voice in his soaring odes of love to Mabel and did that intensify their relationship? What else might have Austin Dickinson have written if he had felt that he could spend his life composing verse instead of financial documents?

So happy birthday, Austin. While so many questions remain about your life, there’s no doubt that your role was central as we ponder answers to the stories of all things Dickinson.